|

|

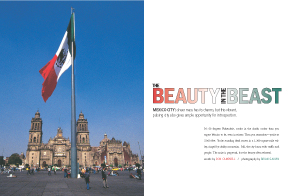

| Mexico City: The Beauty and the Beast |

Photos by Brian Gauvin/Gauvin Photography

Photos by Brian Gauvin/Gauvin Photography

It's 60 degrees Fahrenheit, cooler in the shade, and cooler than you expect Mexico to be,

even in January. Then you remember -- you're at 7,000 feet. You're standing dead center in a

1,240-square-mile valley, ringed by chalky mountains that you can barely see even on a good

day. The heavens are hazy, the air is thick, like paste. Your nose stings, your lips burn by

the end of the day. The city bulges with buildings, traffic, people. The noise is perpetual

and deafening.

You make your way to the place they call Zocalo. Officially it is Plaza de la Constitucion,

but you tell your cab driver "Apreciarķa ir a Zocalo, por favor." He takes you to the heart

of Mexico City. "Aqui," he says. He points out colonial buildings and offices, and wishes

you good luck. You see the 10-acre expanse, a wide, open space at whose center stands the

biggest flag of any nationality you've ever seen. It billows for a moment, long enough for

a snapshot, then luffs. People mill.

Your gaze is pulled north to the Catedral Metropolitana, a 16th century Catholic church.

Its naves, bells and austerity stand in testament to faith, to Spanish kings, to the endurance

of God. But it stands crookedly, as if it's sinking in slow phases, and tilts oddly in your

view, playing tricks on your eyes.

You circle it, approach it, then enter. The church is beyond the pen's ability to describe it.

It is larger than what your eyes can take in. Ornate, mammoth, austere, full of echoes, the

smell of ancient dust and incense, and a strange cacophony of a priest ministering mass to the

repentant and a jackhammer chipping away at restoration. You think about the souls that have

been saved, and lost, the years the walls have absorbed and endured, the solitude of meditation,

and the layers and catacombs of history that dive into the earth below. You begin to sense

something primal.

You move outside. To the east, a peso's throw away, you see the ruins. Templo Mayor. It is

said that at this very place, Mexico was born. Ancient Aztecs, wandering the swampy shores

of a giant lake, founded their own city, Tenochtitlan. Legend holds that those ancients

witnessed here the eagle, snake in mouth, alighted on the cactus. Right here.

You stare. You forget about church, about ruins. You feel electricity, a buzz, a thrum.

You stand where three cultures have thrived. Modern Mexico built on colonial Mexico on top

of Aztec Mexico. Seven centuries, you figure, and you have found its very soul.

THE SQUARE

On what elsewhere would be a quiet Tuesday morning, the area around Templo Mayor hums with

the loud and maniacal street commerce that makes up the day, every day, in Mexico City.

Until you go, you cannot understand the teeming mass of Mexicans who pulse through the

streets like the blood of a body. Young, old, vibrant, infirm, for them this is life.

Small shops line the streets, but bold entrepreneurs snarl nearly every inch of sidewalk

and a portion of the street. For as far as you can see in every direction, people sell

all of life's essentials, and some not so. All manner of home products, fresh fruit, tacos,

toys, CDs, candy, tools. Young men and old women push grocery carts full of ripe oranges

and squeeze them into fresh juice. El Oso shoeshine stands, religious art, knit hats,

knickknacks and tchotchkes. Men chide you to let them guide you, or do carpentry, or read

your fortune. It's a ceaseless sing-song litany of availability, a buyer's-market competition

for your attention, and of course, your pesos. You are giddy.

Set foot in Zocalo, and you immediately notice two things: how old and uneven everything is -

the sidewalks, the buildings' walls, the streets; and the crushing noise level, generated by

the thousands, maybe millions, who frequent this place each and every day, who ride noisy green

buses and taxis, walk, yell, and push through life here.

In its arms, Mexico City holds 22 million people and counting. It's the cultural, political

and spiritual center of the nation. It is commerce and government, poverty and middle class

and upper crust. Millions of cars, thin air and thermal inversions create oppressive pollution.

It is big, ancient, pungent, sharp and aggressive, a city that bulls its way toward tomorrow.

It begins right here in Zocalo.

IT MEANS PINK ZONE

You need a break to steady your legs and nerves. You venture up Paseo de la Reforma, a grand

avenue soon to be grander as work on its restoration nears completion. You find Zona Rosa.

Named for a series of pink facades painted back in the '60s, the Pink Zone is a tight grid of

small streets and low-hanging trees with eateries, chi-chi shops, jewelry stores, art galleries

and swank. Around 6, it erupts with yuppies done with work, street urchins, leathery-skinned

old crones panhandling for change, young teens, hawkers, lovers, and what you are sure are

leftist poets who dress in black and smoke incessantly.

It's a scene you observe with cocktails from a club called Boomers, trendy but cheery,

with sidewalk seating, and live music later in the night. You wander up a side street and

find dinner at a tequilaria called Cielo Rojo. You thrill to the live mariachi music, then

a quintet who play everything, your waiter says, from conjunto to tejano to norteno. You

order an unusual dish that is fajita meat (pollo, chicken, and puerco, pork) but served in

a blistering hot hollowed out stone with legs, like a pestle. It's steamy, succulent and

hellish on the tongue. Rounds of Don Julio tequila and Negro Model beer help. For a Monday

night, the zone is hopping, with street vendors, live music every block, clusters of people.

You only imagine what it's like on Saturday night.

ANOTHER WORD FOR GRASSHOPPER

You discover that Mexico City has many parks, necessary buffer zones from the noise and haste.

West up the artery of Paseo de la Reforma is Chapultepec Park, a 2.5-square-mile haven.

Aztec royalty took refuge here.

You will too, early one morning. Your cab driver, Francisco Barrios, delivers you to the

foot of Castillo de Chapultepec. "There's an elevator," he says, "but it's never working."

So you huff up the hill, passed by joggers and cyclists. Your reward is a fabulous 360-degree

view of the city. Skies are clear, clear as they get, but you still get a whiff of smog and

obscured views of the mountains. It is here where Hapsburg Emperor Maximilian and his wife

Carlotta lived and ruled as Mexico's early monarchs. The castle was home to many of Mexico's

presidents, until President Lazaro Cardenas converted it in 1940 into the Museo Nacional de

Historia for all to enjoy. Its opulence is alarming and its view stunning, as it looks down

Paseo de la Reforma to the grand statue, Al Angel.

You wander through Chapultepec Park and see lakes with rowboats, a giant amusement park

and children's science-and-industry museum, tony restaurants, tall and grand memorials and

statues, and hiking trails. On Sundays, all museums are free. Families frequent then, to

spend the day away from the mayhem. They get the same education you do about Mexico City's

history. You wish you it were Sunday.

OF COYOTES AND BRUSH STROKES

When the beast of the city drives you crazy, you long for the quiet heart of the artist.

Your guide, Antonio Murzia, knows the perfect place, and takes you to Coyoacan, Place of

Coyotes, and a place with just such a heart.

Coyoacan is a quiet burg within the city. Soothed by tacos at El Guarache, near Hildago

Square and the Jardin del Centario, and lifted by strains of strolling ranchero musicians,

you ask your waiter the way to Frida Kahlo's Blue House. He smiles, and points the way.

You amble across the plaza, near the 16th century Parroquia de San Juan Bautista, a venerable

church, and up quiet streets. You walk a few blocks, and enter Kahlo's lifelong home, which

she later shared with her famous husband, Diego Rivera.

Born in Coyoacan in 1907, Kahlo, like her husband, is a national treasure. A tortured soul,

her art is dynamic, rich and vibrant works in oils, charcoal and other mediums, though

colored with enough pain for 10 lifetimes. She and Diego were bohemians, leftists and

freethinkers, enjoying a sense of heightened creativity and a prodigious outpouring of work

up until their deaths in the '50s.

You see the place of the their workaday world, you feel the exquisiteness of their work.

From bedroom to kitchen to studio, you walk among art and memorabilia. You linger in front

of sketchbooks, where their ideas were formed. You imagine the power of a single brush

stroke. You are soothed, and know your $2.50 admission is the best money you have ever spent.

YOU SAY XOCHIMILCO, WE SAY FLOATING GARDENS

Your pulse grows even calmer at Xochimilco, a verdant pocket 45 minutes from downtown. It

is what you expect of Mexico. Small, quaint, picturesque, and wordly famous for its floating

gardens. Antonio deciphers Spanish and Aztec words for you. His English is minimal, your

Spanish less so, but you come to understand of what he speaks. Xochilmilco, he says, means

"place where flowers grow" in the Aztecs' native Nahuatl.

Antonio circles the city, then deposits you at La Tierra de la Flores, which he explains

is roughly Land of the Flowers in Spanish. Acres of brightly colored tejeneres cram an

embarcadero. These long flat gondolas, each with a long central table and chairs, are

made for a party. Juan Flores poles you languidly out into the inky water, part of an

arterial system of canals that measures some 110 meandering miles, fashioned several

hundred years ago from the swampy lake that used to be here, gradually molded off into these

canals with mud and plant.

It is another world. Weekends are a riot of family fiestas, weddings, anniversaries.

Small eateries sell quesadillas and lamb stew. Floating vendors offer beer, pop and food.

Today it is quiet. Modest homes line the shore, with lavish gardens, greenhouses, hanging

plants. You hear unfamiliar birds cheeping and whistling. Roosters crow. The sun glints off

the water. Juan sees a ripple. "Pescado," he says as lanquidly as he poles, and rattles off

the names of native fish. The trees come down to the water's edge. You watch small farms role

by. Dogs bark lazily. You lie on the bow, your face in the sun, and begin dreaming in

Spanish.

At the dock, Antonio insists you visit the Museo Dolores Olmeda Patino. You comply. A

survivor from the 16th century, this hacienda of Dolores Olmeda, a one-time mistress of

Diego Rivera, is a gallery housing a delicious collection of the artist's work and that

of his wife, Frida Kahlo. Among the grounds of fragrant citrus trees, peacocks, bougainvillea,

well-kept quarters and rare dogs, you can stand a paintbrush-length's away from their works.

Diego's early works, up until the mid-'30s, fill you wit awe and wonder. His later works,

though strong and vibrant, are more confusing. Yet you understand his greatness, why he lives

on, why his murals adorn the walls of the presidential palace, why he traveled in the circles

of legends.

SAY ADIOS

You head for one last dinner down in Zona Rosa, after watching the light fade on the plaza of

La Diana Cazadora. You hover on a street corner of this giant roundabout, waiting for the

magic light of dusk, watching cops direct the traffic, known here as The Monster. Driving in

Mexico City is a competition for space, you decide. It's not for the faint of heart. An armada

of motorcycle cops pulls up suddenly and shuts down the plaza, stopping all traffic. The

Monster howls its displeasure in an angry torrent of honking.

You watch a family, mostly brothers and sisters you think, work the window-washing angle at

a stoplight. It's common at stoplights to be hounded with newspapers, phone cards, lottery

tickets, gum, trinkets and junk.

One young woman, a child really, cradles her little sister to her chest, and wanders out

in traffic with her kin. They are earnest, and never let a stoplight go by. Maybe 30 minutes

later, the little sister has fallen fast asleep, and the young girl lays her on a concrete

bench nearby, after spreading a layer of newspaper. She wraps her tightly, and protects her

with blankets, coats and a barrier of daypacks, and goes back to work. It tears your heart out.

You finish dinner, and you see the young girl again, still working, as you walk past. It is

dark. The baby is still asleep on the bench. You tap the young girl on the shoulder and say

above the din of traffic, "Aqui, para la niña," and hand her a pile of pesos. She looks at

you quietly and says, "Gracias," and slips back into traffic.

More than from your own city and your own life, you feel the naked slap of hard reality here.

You know that later on, thousands of miles away, you'll lie in your bed, your stomach (and life)

full, and think about these kids, and the thousands like them, for whom every day is as rugged

as this one. You'll think about the traffic and the noise and the beating heart of this city,

and feel it vibrate. Everyday at 6 p.m. the Mexican army will march out to take down the flag

in Zocalo. The ghosts of Tenochtitlan will retire to their graves. The protestors will protest.

The merchants will go home, the yuppies will grab dinner and shots of tequila. Seven centuries,

you figure, and the heart still beats.

You already can't wait to come back.

Don Campbell is a frequent contributor to World Traveler magazine.

| |

|